|

Bridging one's political work with one's artistic practice in a meaningful way is not easy. There are three general ways artists have built this bridge:

As my own practice has progressed, I have been trying to move from using just method #1, that is, making art with some political or social justice content, to using methods #1 and #2. And this past Sunday, Jan 28, I had the chance to finally bring an oral history project I conducted in Barre, VT as part of my book/zine project, Metamorphic: The Transformation of Work in Granite Town, to some amazing working-class activists and organizers in Barre, VT at the VT AFL-CIO COPE Conference. The conference was held in the Old Socialist Labor Party Hall in Barre, a perfect space for both the conference and my project. I called my presentation "Voices and Contours of Labor: Notes and Drawings from My Oral History Project in Barre, VT". "COPE" stands for the "Committee on Political Education". At the VT AFL-CIO COPE Conference, that usually translates to talking about issues that concern labor that are currently moving through the legislature. So, bringing interdisciplinary art into such a space can seem like a tangential diversion that may be unwelcome -- but, fortunately, that was not at all the case. After all, political education can encompass so much more than electoral politics. While I completely understand the importance of educating ourselves on what is going on in our state's legislature and putting pressure on our representatives to get labor-friendly results, I was also taught a broader and deeper understanding of political education through my work with the Vermont Workers' Center, The Poor People's Campaign, and the Popular Education Project (PEP). In doing political education work with these organizations, I learned about the fundamental social forces of capital and labor under capitalism and how they move and interact. Understanding this allows us to see not only the possibilities right before us but also those of the future. So, despite how out of the box my art and research is in such a context, I went and ahead and did my presentation. I explained how I became interested in Barre because of its radical labor history and because it is a case study in deindustrialization -- before the term even came into popular parlance. Barre, like all cities that are commonly associated with the term deindustrialization, was once known as a center of industry but is now more known for its stagnant economy and poverty. It is a case study in the tendency of capital to reduce labor costs. There are many ways capital has achieved this, but the most powerful way by far has always been through technological development. Globalization, which is also often cited as a means of reducing labor costs, is dependent on developments in information and transportation technology, without which it would be impossible to coordinate free trade across the globe. At the same time, in the midst of deindustrialization and rapid technological development, is the possibility for freeing up more of our day from waged work. I continued to explain that I wanted to go beyond what other oral historians had done when interviewing people about work: I wanted to not only ask them how they felt about the work they did, but how they would feel about not working -- or, at least, not working as much. Automation will continue disrupt the economy; and, with technology becoming increasingly capable of replacing everything from unskilled to highly skilled labor (as adeptly pointed out by Martin Ford in his book The Robots Are Coming), work as we know it in the form of the the full-time job and the 40 hour work week may become more of a rarity in the job market. That means we may have to rethink our relationship to waged work if we don't want masses of people to be left out in the cold void of long-term to permanent unemployment. Then, after having talked to everyone about automation, the future, and robots, I brought it back to Barre with the oral histories I conducted there. Given my time limitations, I shared brief quotes from three different people working in Barre, VT, extracted from hours of recorded material. Overall, some people readily welcomed the prospect of a "postwork" society with more free time for workers. Some less so. Regardless, most expressed a desire to work less. Here is what I shared: Ellen, Early Childhood Educator “I need to be working and making a difference. And frankly, if I didn't have to work and I could spend as much time doing whatever I potentially was qualified to do, I would totally do something that I feel passionate about.” “I think automating all jobs is a terrible idea. I think that's not allowing us to be human anymore. I do feel like a lot of the work that I've done has been very purposeful. It's not just about going to work to make the paycheck. You're doing what was meant for you to do, the reason why you were put here, essentially.” “Even if I won the lottery, maybe at first I would take a break for a period of time from work, but I would not want to just retire for the rest of my life.” Gampo, Granite Carver/Finisher “If my needs were sort of more balanced, maybe I'd be more generous with the commission work. And that would be kind of cool actually. Because right now in capitalist society, you kind of go after lots of money, like is it big enough? You have a very targeted capitalistic mindset.” “I think when people's needs are met, it would be more sort of communal. I don't know if communal is the right word. It would be where people would just have a little more care for each other instead of competition.” Sarah Miller, Diversion Case Manager  “My parents have been retired now for, I guess, my mom's been retired for 18 years and my dad was retired for 18 years before he passed. They have really rich lives. My dad volunteered, my mom volunteers. She's a fiber artist. She crochets, she knits, she does embroidery and wins awards for it. She quilts and she goes to church and she has really deep relationships. I feel like more of her life is meaningful. She has more meaningful moments in that regard.” “It would be awesome if we had four day weeks. Every time I feel like three days is so much better to reset yourself. I just wish we didn't have to do it so much, that there weren't so many trappings, because I don't think the purpose of us being on this Earth is to work. I think we're just supposed to be here.” As you may have noticed, I haven't finished the digital drawings of all the interviewees yet: Sarah's is still in-progress. So what kind of response did I get for taking everyone on a sort of wild ride into possible futures merged with good old fashioned oral histories? How well was I able to bridge my political work with my artistic practice? Well, I can't say for sure what everyone was really thinking. But, people seemed pretty interested, and my presentation stimulated some good conversations over lunch. The conversations confirmed my belief that people are hungry for political education that is artistic, interdisciplinary, and experimental -- even when it comes to liminal subjects such as automation and robots that seem to sit somewhere between reality and science fiction. I grant that my artwork may not be categorized as material for political education in the strict sense of being designed explicitly to explain certain campaigns or concepts. However, I think political art that is brought into political spaces (that is, art that at least combines methods #1 and #2 for bridging political work and art), can be a powerful form of political education. It can encompass more than a single campaign or issue and get us all to think about that which we take for granted -- such as the fact that we must sell our labor power in order to survive. "The mental battlefield is littered with old and entrenched values and ideas", writes Willie Baptist in Pedagogy of the Poor, a brilliant political educator and poverty scholar whom I've had the pleasure of meeting (Baptist 163). In the context of my project, I am dealing with old values and ideas around work, in which waged work is the only kind of recognized work and reigns supreme over all the other labor we do for each other and ourselves; over taking care of our children, family, and friends; over volunteer work in our community; over the work we do to educate and cultivate ourselves. "'Plowing the field' of old ideas is indispensable to "planting seeds" of new ideas" (Baptist, 163). Waged work doesn't have to monopolize so much of our time. The question is what would we do and what would become if we had more free time? Major structural changes in our economy are on the horizon. Radical labor leaders in Barre, VT fought for the 8 hour work day, and, almost a hundred years later, we are long due for another reduction in the workday while still retaining our standard of living. That's why for me, as a working class artist, bridging politics and art is not only possible but necessary for a progressive and just future.

1 Comment

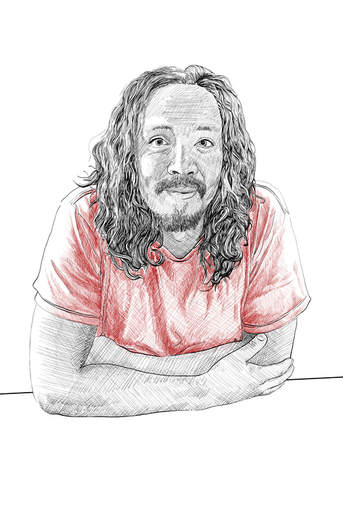

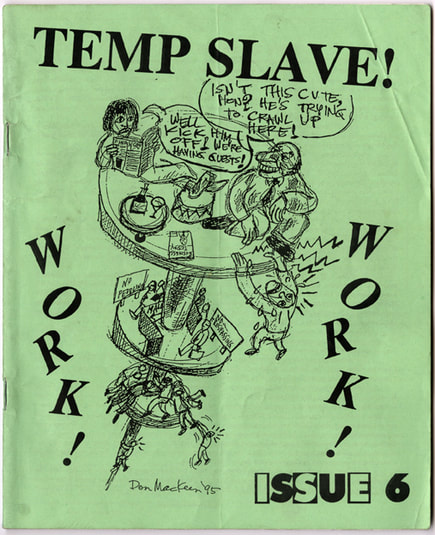

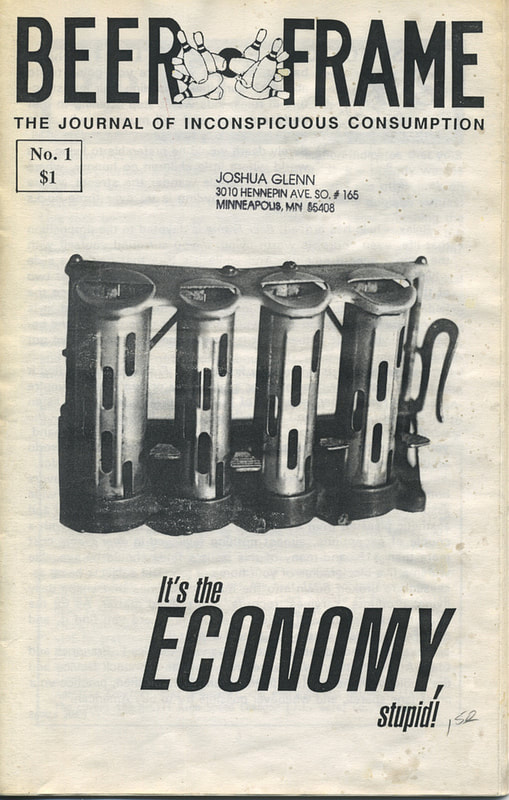

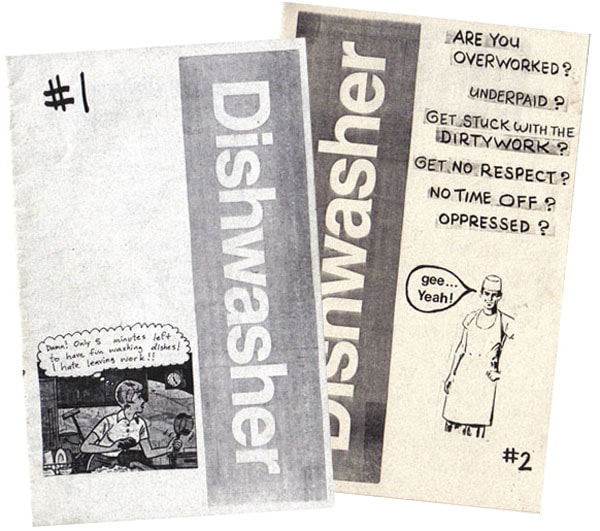

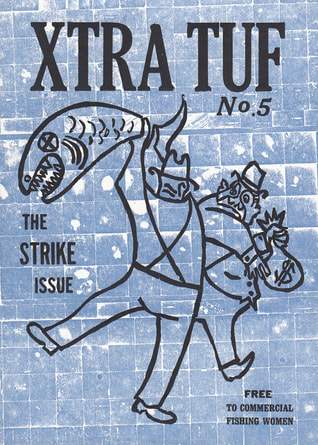

Coming from a background in the visual arts, I’ve always liked the idea of working with text and image, but it has taken me some time for me to think about what relationship between these two forms of communication would most powerfully give voice to what I care about. To better ground myself in the world, including the world of prose and ideas, I took a break from my visual art practice altogether. Some years later, I found myself working at an institution, Goddard College, that fully embraced an interdisciplinary approach to artistic inquiry. After a year of experimenting and searching at Goddard, I realized the way into developing a practice based on text and image has been around a long time: the way was through zine-making. First, putting text in relation with images is something that inevitably happens, even within a strict visual arts practice. Inevitably, the artist has to contextualize it with words in order to be taken seriously, and, if it is being shown, someone is going to talk or write about it eventually. Some artists may shun text for the way it delimits an image, but it is inescapable. My reason for moving towards a practice that integrates text and image, with an increasing emphasis on the former, is precisely because I want it to be somewhat delimited. Of course, I don’t want to be didactic, but instead of offering a wide channel for interpretation, I want to offer a deep channel -- breadth and depth, ideally, but if I have to choose, I choose depth. I want to make work that is moving, critical, and thought-provoking. But I want to make work that is clear and sure of itself such that it cannot be appropriated by those who would wish to reduce it to milquetoast. Even more, I want to create art that gives history and agency to those who are the makers of history: the working classes. Those are the abstract formal reasons for my turn to text, but the political nature of my subject matter naturally inserted itself into the history of zine-making, or, more broadly, the making of pamphlets and leaflets. Zines, while mostly known today for their association with the riot grrrl subculture, are part of a wider history of self-publication, harking back to political pamphlets and leaflets. Within the United States, one of the most well-known political pamphlets is Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, which made a popular and forceful argument for the independence of the United States from Great Britain. Common Sense was read and distributed widely; it found audiences everywhere from drawing rooms to taverns, its words heightening the zeal for self-determination and freedom. Surpassing the influence and fame of Paine’s Common Sense is arguably The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx. In February 1848, The Communist Manifesto began as a 23-page pamphlet published by the Workers' Educational Association: this manifesto became the seed of not only one revolution but many and continues to be read in revolutionary movements to this day. Fast forward, Zines and zine culture, like the political pamphlets and leaflets that came before them, continued the tradition of printing dissident ideas and voices. However, unlike the two aforementioned political texts, the zine cultures that arose in the 70s, 80s, and 90s that are most familiar to us today were less interested in mass distribution and appeal than they were in cultivating subcultures in which individuals with identities and politics repressed by or adversarial to those of the mainstream could find reprieve through self-expression. The zines coming out of what was labeled the riot grrrl subculture, for instance, appealed largely to third wave feminist sensibilities by emphasizing the diverse, individual experiences of sexism. As Stephen Duncombe, Professor of Media, Culture and Communications at NYU and author of Notes from the Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture, writes “Zines put a slight twist on the idea that the personal is political. They approach political issues from the state to the bedroom, but they refract all these issues through the eyes and experiences of the individual creating the zine.” Rather than political manifestos aimed at fomenting a societal revolution, zines coming out of the subcultures such as riot grrrl often used their medium to instead create intimate communities of support and resistance. One of the first zines I picked up as a teen hanging around at punk shows was Support by Cindy Crabb and Doris Zine. The zine is composed of a collection of written and collected pieces of advice on supporting survivors of sexual abuse and preventing sexual violence. It has helped me understand both myself and others. It has also taught me how to become a better listener and friend -- again, to both myself and others. It was written to be an invaluable healing tool. It was not written to analyze the long history and structure of patriarchy in an attempt to outline how it may be overthrown. A simple wikipedia search on zines will highlight their connection to riot grrrl and a few other subcultures, but less known is the frequency with which zines were used to protest the conditions of work under capitalism, made worse by the shrinking of the welfare state and the rise of neoliberal, pro-market politics beginning in the 70s. As a wage slave educated in Marx’s political economy who entered the labor market in the midst of the 2008 financial crisis, I knew that the increasing sense of impoverishment and alienation I experienced was shared by many and part of paradigmatic shift in capitalist development that was leading us all towards a more precarious future for ourselves and our planet. I also knew this had to inform the content and form of my renewed artistic practice. I had already started my serial book project, Metamorphic: The Transformation of Work in Granite Town, to be released chapter by chapter as zines, before I knew about such gems as Dishwasher Pete, Welcome to the World of Insurance, Temp Slave, and ExtraTuf, all of which offered varying acrimonious and cathartic critiques of work and the work ethic. It was the Stephen Dumcombe’s Notes from the Underground that introduced me to the world of zines about work. According to Duncombe, the zine was really the perfect medium to channel the frustrated creative and intellectual energies of workers disillusioned with their job and the American Dream of upward social mobility. “In zines, writers present the real story of the work they do,” writes Duncombe, “...cutting through the crap...about the bright future in the high-tech age.” Zines, being self-published and easy to produce, offer space to dissenting voices who may otherwise find themselves censored or dismissed by mainstream media outlets charged with upholding the ideology of the work ethic. With wages stagnating, worker power in the form of unions diminishing, and the constant deskilling of labor through technical and organizational innovations, zine writers feel there is no “dignity of work” to preserve. But instead of grieving their low-pay and lack of power at work, many zine writers mock the hypocrisy of the social and economic relations at work. In a labor market where the company and the boss expect their workers to give their all but offer little in return by means of security, benefits, and wages, a mocking, apathetic, or hostile reaction is not surprising. A brilliant example of cynical humor illustrating this attitude shows up in a column titled “Problems and Solutions” in Dishwasher Pete: “PROBLEM: You’ve been breaking a lot of dishes at work” “SOLUTION: What’s the problem?” That said, zine writers are not against work in the abstract; contra to the DIY aesthetic present in many zines which can sometimes give them an “unpolished” look, creating zines requires a lot of intense focus and work. Unlike the day jobs that become the subject of many zine writers derision, zine creation is an act of unalienated labor that is enriches the heart and mind and is therefore relished. However, compared to more traditional hobbies, zines self-consciously emerge from adversarial conditions. An interview with Pinto editors Sara Lorimer and Paul Schuster clearly makes this connection: “Sara: You know I’d never thought about doing a zine until I started working at that awful record store. There’s gotta be some sort of connection there -- between that being such a stifling place and needing an outlet for creativity. Paul: Yeah, maybe it’s a reaction to the shitty working environment we were all subjected to…” Zine writers, whether or not they were writing about work, are carving out their own “little world, in which [they] can experience the revolutionary pleasure of thinking for [one]self”, writes Mickey Z, creator of Flaming Crescent zine. When I started my book project and decided to release each chapter as a zine, I also wanted to make space for the complicated -- and sometimes angry -- thoughts and feelings we all have about our jobs but must bury in order to appear as functional workers and citizens in a capitalist society. But I also wanted to connect these feelings to the why: Why are so many workers feeling angry and alienated at work? Why is social mobility decreasing and inequality increasing? I’ve read plenty of explanations from mainstream economists, from Thomas Friedman to Robert Reich, and while they may at times make valid points, their structural analysis falls short -- mainly due to their incomplete understanding of how value is created -- when compared to the master of political economy, Karl Marx. More importantly, Marx developed his theory on the basis of those very questions, as Terry Eagleton writing for the Chronicle of Higher Education has pointed out: “There is a sense in which the whole of Marx's writing boils down to several embarrassing questions: Why is it that the capitalist West has accumulated more resources than human history has ever witnessed, yet appears powerless to overcome poverty, starvation, exploitation, and inequality? What are the mechanisms by which affluence for a minority seems to breed hardship and indignity for the many? Why does private wealth seem to go hand in hand with public squalor?...” I’ve read through Capital and other works by Marx by myself and with others. And, as much as I personally loved reading almost a thousand pages critiquing capitalism, I know that we first experience capitalism in a very personal way. We need to awaken both the heart and the mind. But while we may first enter the realm of the political through our own experiences, through our heart, we will never move beyond individual transformation if we don’t connect it to a larger analysis. It is with a unifying theory that the personal becomes political. So here I am, releasing my first series of zines. Of course, I could just as easily write a series of blog posts, like this, which shares the spirit of the DIY confessional with zines. In fact, many have said that with blogging, the zine is irrelevant in this day and age. And yet, I couldn’t disagree more. Aside from the rich history of zine making, printed books and zines are more intimate; they can be touched; they take up space. A blog is at once everywhere and nowhere. It is easier to curl up with a zine and let oneself open up to it like an old friend. On paper, there aren’t the distractions of dozens of open tabs and apps. Not to mention, my inner teenage punk is totally excited about this -- and I hope you are all too. For all that, while this project is will situated in the history of zines, I also hope to go beyond my own “little world” of autonomous thought and, instead, create many, connected worlds for free thought through the collection of oral histories from workers located in Barre, VT, which will constitute one of the chapters of my book and a zine issue. I’ve chosen Barre not only because it has shaped the place where I currently live but because it has a unique, radical history of class consciousness and organization with the aim of creating a freer world. They have questioned the very notion of a world where the many had to work so hard to live no matter how much wealth they produced for others. They knew that justice did not equal just having a job but having control over that job; and, more importantly, having free time to do all the unwaged caring, learning, and loving that are necessary for living as a human being. Through original illustrations, collected interviews, and personal meditations at the intersection of geology, political economy, and psychology, Metamorphic will make the personal political.

|

AuthorI am an interdisciplinary artist who brings together images, narratives, and social theory to reveal the lived and imagined systems that construct our lives. Archives

September 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed