|

Bridging one's political work with one's artistic practice in a meaningful way is not easy. There are three general ways artists have built this bridge:

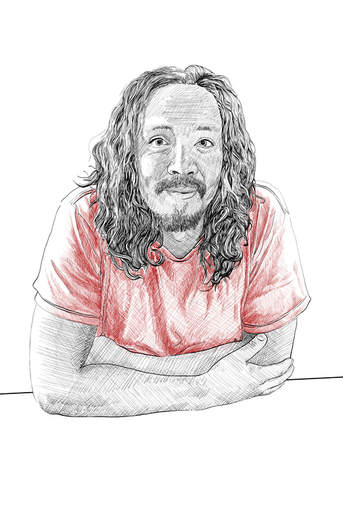

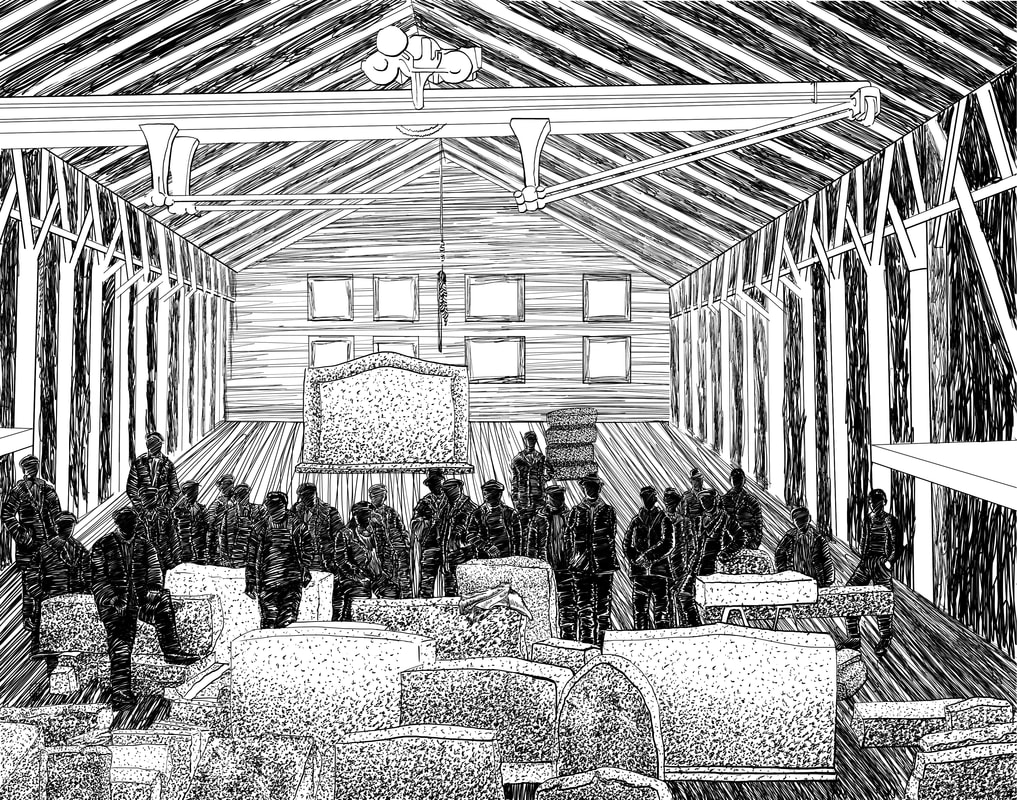

As my own practice has progressed, I have been trying to move from using just method #1, that is, making art with some political or social justice content, to using methods #1 and #2. And this past Sunday, Jan 28, I had the chance to finally bring an oral history project I conducted in Barre, VT as part of my book/zine project, Metamorphic: The Transformation of Work in Granite Town, to some amazing working-class activists and organizers in Barre, VT at the VT AFL-CIO COPE Conference. The conference was held in the Old Socialist Labor Party Hall in Barre, a perfect space for both the conference and my project. I called my presentation "Voices and Contours of Labor: Notes and Drawings from My Oral History Project in Barre, VT". "COPE" stands for the "Committee on Political Education". At the VT AFL-CIO COPE Conference, that usually translates to talking about issues that concern labor that are currently moving through the legislature. So, bringing interdisciplinary art into such a space can seem like a tangential diversion that may be unwelcome -- but, fortunately, that was not at all the case. After all, political education can encompass so much more than electoral politics. While I completely understand the importance of educating ourselves on what is going on in our state's legislature and putting pressure on our representatives to get labor-friendly results, I was also taught a broader and deeper understanding of political education through my work with the Vermont Workers' Center, The Poor People's Campaign, and the Popular Education Project (PEP). In doing political education work with these organizations, I learned about the fundamental social forces of capital and labor under capitalism and how they move and interact. Understanding this allows us to see not only the possibilities right before us but also those of the future. So, despite how out of the box my art and research is in such a context, I went and ahead and did my presentation. I explained how I became interested in Barre because of its radical labor history and because it is a case study in deindustrialization -- before the term even came into popular parlance. Barre, like all cities that are commonly associated with the term deindustrialization, was once known as a center of industry but is now more known for its stagnant economy and poverty. It is a case study in the tendency of capital to reduce labor costs. There are many ways capital has achieved this, but the most powerful way by far has always been through technological development. Globalization, which is also often cited as a means of reducing labor costs, is dependent on developments in information and transportation technology, without which it would be impossible to coordinate free trade across the globe. At the same time, in the midst of deindustrialization and rapid technological development, is the possibility for freeing up more of our day from waged work. I continued to explain that I wanted to go beyond what other oral historians had done when interviewing people about work: I wanted to not only ask them how they felt about the work they did, but how they would feel about not working -- or, at least, not working as much. Automation will continue disrupt the economy; and, with technology becoming increasingly capable of replacing everything from unskilled to highly skilled labor (as adeptly pointed out by Martin Ford in his book The Robots Are Coming), work as we know it in the form of the the full-time job and the 40 hour work week may become more of a rarity in the job market. That means we may have to rethink our relationship to waged work if we don't want masses of people to be left out in the cold void of long-term to permanent unemployment. Then, after having talked to everyone about automation, the future, and robots, I brought it back to Barre with the oral histories I conducted there. Given my time limitations, I shared brief quotes from three different people working in Barre, VT, extracted from hours of recorded material. Overall, some people readily welcomed the prospect of a "postwork" society with more free time for workers. Some less so. Regardless, most expressed a desire to work less. Here is what I shared: Ellen, Early Childhood Educator “I need to be working and making a difference. And frankly, if I didn't have to work and I could spend as much time doing whatever I potentially was qualified to do, I would totally do something that I feel passionate about.” “I think automating all jobs is a terrible idea. I think that's not allowing us to be human anymore. I do feel like a lot of the work that I've done has been very purposeful. It's not just about going to work to make the paycheck. You're doing what was meant for you to do, the reason why you were put here, essentially.” “Even if I won the lottery, maybe at first I would take a break for a period of time from work, but I would not want to just retire for the rest of my life.” Gampo, Granite Carver/Finisher “If my needs were sort of more balanced, maybe I'd be more generous with the commission work. And that would be kind of cool actually. Because right now in capitalist society, you kind of go after lots of money, like is it big enough? You have a very targeted capitalistic mindset.” “I think when people's needs are met, it would be more sort of communal. I don't know if communal is the right word. It would be where people would just have a little more care for each other instead of competition.” Sarah Miller, Diversion Case Manager  “My parents have been retired now for, I guess, my mom's been retired for 18 years and my dad was retired for 18 years before he passed. They have really rich lives. My dad volunteered, my mom volunteers. She's a fiber artist. She crochets, she knits, she does embroidery and wins awards for it. She quilts and she goes to church and she has really deep relationships. I feel like more of her life is meaningful. She has more meaningful moments in that regard.” “It would be awesome if we had four day weeks. Every time I feel like three days is so much better to reset yourself. I just wish we didn't have to do it so much, that there weren't so many trappings, because I don't think the purpose of us being on this Earth is to work. I think we're just supposed to be here.” As you may have noticed, I haven't finished the digital drawings of all the interviewees yet: Sarah's is still in-progress. So what kind of response did I get for taking everyone on a sort of wild ride into possible futures merged with good old fashioned oral histories? How well was I able to bridge my political work with my artistic practice? Well, I can't say for sure what everyone was really thinking. But, people seemed pretty interested, and my presentation stimulated some good conversations over lunch. The conversations confirmed my belief that people are hungry for political education that is artistic, interdisciplinary, and experimental -- even when it comes to liminal subjects such as automation and robots that seem to sit somewhere between reality and science fiction. I grant that my artwork may not be categorized as material for political education in the strict sense of being designed explicitly to explain certain campaigns or concepts. However, I think political art that is brought into political spaces (that is, art that at least combines methods #1 and #2 for bridging political work and art), can be a powerful form of political education. It can encompass more than a single campaign or issue and get us all to think about that which we take for granted -- such as the fact that we must sell our labor power in order to survive. "The mental battlefield is littered with old and entrenched values and ideas", writes Willie Baptist in Pedagogy of the Poor, a brilliant political educator and poverty scholar whom I've had the pleasure of meeting (Baptist 163). In the context of my project, I am dealing with old values and ideas around work, in which waged work is the only kind of recognized work and reigns supreme over all the other labor we do for each other and ourselves; over taking care of our children, family, and friends; over volunteer work in our community; over the work we do to educate and cultivate ourselves. "'Plowing the field' of old ideas is indispensable to "planting seeds" of new ideas" (Baptist, 163). Waged work doesn't have to monopolize so much of our time. The question is what would we do and what would become if we had more free time? Major structural changes in our economy are on the horizon. Radical labor leaders in Barre, VT fought for the 8 hour work day, and, almost a hundred years later, we are long due for another reduction in the workday while still retaining our standard of living. That's why for me, as a working class artist, bridging politics and art is not only possible but necessary for a progressive and just future.

1 Comment

The following is a selection from Metamorphic: The Transformation of Work in Granite Town, Chapter 1 "Everywhere and Anywhere". The entire chapter has been released as a zine issue, which you can order from me by contacting me. The zine is a suggested $1-2 donation plus shipping.Metamorphic rocks have resided in different geological settings in their journey of becoming what they are. They become their own unique hybrids of the places they’ve lived. They record more than a journey; they record change. Not all rocks are metamorphic -- granite is not a metamorphic rock -- but all kinds of rocks can become one. “All science would be superfluous if the outward appearance and the essence of things directly coincided.” - Karl Marx The empty shops, boarded up houses, and smokestacks of Binghamton and Baldwinsville, New York -- most of them silent and statuesque in their new function as memorials of another time -- impressed my childhood mind as enigmas. At one time, they contained and supported lives. Why didn’t they anymore? I’d take long, clandestine bike rides out to them, get close to their facades, daring them with my gaze to reveal the calamities they contained; I intuited the present dangers of drugs and violence that grew in their darkness to be natural extensions of the troubles that led to their current state of dereliction. But I never went in. I never uncovered their particular histories. My grandparents used to work behind some of those factory walls. Through their toil, they fed and housed a family, but the work also gave them much pain, which was made known through frequent complaints of achy hands, backs, and feet from standing on concrete floors all day, making the same motions over and over in sync with the machines. But much of their interior lives and feelings were hidden behind a wall of stoicism. In school, I was taught that we are on a one-way journey called progress. The strained optimism of my parents tried to validate this claim. When I found my mom crying late one night after she finished her shift at Burger King, the only job she could find at the time when our family desperately needed the extra money, the idea of progress became a prevarication that sank into the pit of my stomach. I knew a little about how it must have hurt because of the cruel assumptions my peers made about her and, by extension, me -- namely, that we were struggling because we deserved to be. My mother is bright. She won awards for her mathematical abilities in school, but she did not have the privilege of a college education. From then on, I learned to see the contradictions in everything. When I ended up in Central Vermont eighteen years later, the neat towns nestled in between the mountains appeared as if they magically arose sui generis without the powerful force of industry. After almost six months of unemployment I found myself working as a VISTA - a Volunteer In Service To America. Vermont’s Twin Cities, Montpelier and Barre, became my home. I lived most of my life in cities where people always outnumber animals, and perhaps that was true of these small towns as well, but it certainly didn’t look like it. Montpelier was the state’s capital, at least, giving it importance by default. Barre was much more mysterious and obscure. Up and down main street, you find the standard small town America offerings alongside a smattering of creative outlets and stores that have somehow withstood the test of time: a gas station every several blocks, a dollar general, a couple convenience stores, a mechanic’s shop, car parts stores, hardware stores, a diner, and a couple of nicer restaurants and shops that probably mainly serve folks from out of town, cooperative artist’s studios and a gallery, a shop for shoe repairs, and a shop for sewing services. Just driving through Barre, you wouldn’t think there is this big hole in the ground nearby that birthed some of the most revered buildings and monuments in history, some of them sitting in Washington, DC: the Smithsonian Institution, Union Station, and the General William Tecumseh Sherman Memorial which is right next to the White House. Or that its granite can be found on almost every battlefield and national cemetery in the nation. Or that it once churned out an enormous amount of money and profits -- enough to make this town into a capital of industry, the Granite Capital of the World. Such auspiciousness drew people from the other side of the ocean, predominantly Italy, Scotland, and Spain. The cost of this outward progress was paid in flesh: the quarry owners swallowed young men whole in their pits and sheds. Widowed wives had to hustle to keep their families alive, running shops and restaurants (sometimes out of their own homes), taking in boarders, furtively making grappa and spirits for the wealthier clientele coming in from neighboring Montpelier, bearing the death of their husbands in the constrained silence of hard labor. There are hints of this history, even on Main Street: a restaurant named “The Quarry” and a statue of an Italian stone carver dedicated to all the workers in the industry. The statute reads as a memorial, but the granite industry is not wholly dead in this town. The traffic whirs by with threatening speed -- commuters travelling between the twin cities, not heading to the quarry or manufacturing plant. I go against traffic towards Graniteville, where Rock of Ages -- now owned by the Canadian company Polycor, Inc, which owns 32 quarries across the North America -- still operates a memorial manufacturing plant and a quarry. Idling at a traffic light, a man holds a cardboard sign that reads “Homeless, need help until SSDI comes in. Every bit helps.” A large, black crow gallantly flies ten feet above me, carrying a large stick in its beak. She or he -- in the society of crows, there aren’t rigidly defined gender roles when it comes to homemaking -- is trying to build a home in which to raise the next generation. Half a mile further down the road, a couple of construction cranes are at work fixing power lines near a subdivision of homes. For us, nesting season never ends. I continue driving. The sky has been relentlessly gray today. Gray skies have a way of quieting everything around you. Nature pulls a blanket of clouds over us and asks us to rest. But, of course, we cannot. We need to make things, make money, make nests. The crow must do this, must live day by day, but even with all of the extra stuff we make, all this surplus, most of us also live this way. There are only a few branches on the road around us, but, sequestered away in the woods there are a countless number of them. Away from the town, ensconced in a congregation of trees stands a large generic-looking modular building, the Rock of Ages manufacturing plant. The Visiting Center, with its stylish modern-looking architecture of sweeping geometric shapes that are slightly distorted for a postmodern yet conservative effect, contrasts with the factory, which is like any other in its extreme efficiency of form. Tourism and work. Luxury and functionalism. Consumption and production. Today, I am the tourist, the consumer. Tomorrow, I will work and produce -- not here, but as a secretary of sorts at a small college. I walk up to the Visiting Center first and see through the windows that it’s very dark inside. I give the doors a try. They are locked. No signage, hours, or writing is present on the door. Perhaps I have the wrong entrance? Walking around its circular structure, I step off of the portico made, of course, of granite and onto the green-brown earth that sucks me into its wet body. Another door and a little sidewalk tell me this is the main entrance. It is also locked, but there is a sign this time reading “The Visiting Center will be open starting May 15. All other visitors are welcome to go to the self-guided factory tour next door.” So that is where I go. An effective sign. The self-guided tour entrance opens into a small lobby with a video on a loop displayed on a mounted flatscreen TV. Old and new advertisements for Rock of Ages graves, or “memorials”, flank the TV on both sides. In the video, a couple talks to me in terms of “we”. The man and the woman are white, in their 60s, wealthy as indicated by their dress and the fact that they are shopping for grand, ostentatious mausoleums. The mausoleums reach for the grandiosity of the Parthenon, for the height of Greek architecture. They are proud, exuberant -- but lest one think their sumptuous taste be an unflattering sign of egotism, the couple looks at me from the screen and says, “We want a beautiful place for our children to remember us in.” The couple gets a form of immortality -- guaranteed by the Rock of Ages Certificate of Craftsmanship -- and the next generation gets a memory, a heritage, a sense of pride. Leaving the lobby, I walk up a flight of stairs to the observation deck where I will be able to see the entire factory floor from above. Here I was met again with the monotonous buzzing which I noticed when I was outside but almost forgot in the quiet lobby with the nice couple endlessly shopping for their memorial. In the video, the couple went to the factory floor, too, showing a subdued admiration for the quality and skillfulness of the machines and workers. I carried that feeling in with me when I walked up to the observation deck. But for the first several minutes, all I could do was stand stunned. It was the grinding and droning, the tickling of dust in my nostrils, the smells of wood and oil -- of industry acting on the senses. A wall of pictures, text, and a diagram told me what was going on before me through faded paper and frames than hung crooked and tired on the wall. Over 200,000 square feet spread out below me, crowded with stones, mammoth ventilation systems, little metal sheds with computer terminals, columns laid on the floor for mausoleums, modest headstones ready for shipment with paperwork strewn across them. In the right-hand corner closest to the observation deck is an area that resembles an artist’s studio and, indeed, this is where the few remaining carvers work. Naturally, Rock of Ages wants its visitors to see this area the most clearly. Tucked away far from the purview of the tourist, the slow back a forth motion of a machine above a steel bed tells of an automatic polishing machine. Customers want to see that care -- that a human touch -- is involved in this most solemn of purchases. We want some distance between ourselves and the machines, because it is becoming clearer and clearer with every innovation that they, and not our children, are the future.

|

AuthorI am an interdisciplinary artist who brings together images, narratives, and social theory to reveal the lived and imagined systems that construct our lives. Archives

September 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed