|

When I began collecting oral histories of people's working lives in Barre, VT this past summer, the work of James C. Scott percolated into my mind. James C. Scott is a political scientist and anthropologist who is perhaps best known for theorizing the politics of everyday resistance, as opposed to major historical events, such as a outright rebellion or revolution. These days, the word "resist" has become popular among those who are opposed to Donald Trump, his administration, and his policies. While resistance to his barbarism in all of its myriad forms is needed, resistance is something that all oppressed people have been practicing since the very first class societies arose. Too see this, and how we may locate resistance in the oral histories of working people, first we need to understand the theoretical framework Scott developed in order for scholars and others to be able to do just that. Central to his theory are his concepts of public and hidden transcripts. Public transcripts are those actions and communications which we feel compelled to perform in the face of power, that is, domination. For those in power, the dominating/ruling class, the public transcript is that which must be performed in order to enforce their power over subordinates and affirm their power among their peers. A common example of this may be a boss being harsh or taking extra punitive measures with their employee to make "an example" out of them. For those lacking in power, the dominated/oppressed group, a public transcript is that which must be performed in order to demonstrate their obsequiousness. Unlike the dominating class, the oppressed have a lot more at risk if they fail to perform the public transcript: they risk their jobs, their livelihood, and, in certain situations such as slavery, their lives. Hidden transcripts are all the myriad of mostly prosaic ways in which power, and thereby the public transcript, is critiqued or challenged. To continue with the examples I've just outlined, a hidden transcript of the dominating/ruling class might be revealed in the boss lamenting to a trusted friend that they would like to be lenient but fear further insubordination or being perceived as weak. For the dominated/oppressed class, they might confide to their friends or coworkers that they wish they could've told the boss off or just walk right off the job. Instead, because of the threat to their livelihood, they had to absorb the criticisms and do as the boss said. These are, of course, grossly simplified situations made to clearly communicate the fundamental dynamics of these concepts. It is important to understand that hidden transcripts are not only found in speech acts. Non-verbal actions may also indicate the performance of a hidden transcript. For example, let's say our worker was being disciplined for shutting down a social media account that was committing hate speech but nonetheless didn't quite violate the platform's community policy. The worker could acquiesce temporarily, but decide to continue to shut down accounts spewing hate speech and claim ignorance of policy and request further training if they are reprimanded again. The book in which Scott elucidates these concepts, Domination and the Arts of Resistance, includes many other excellent examples of non-verbal performances of a hidden transcript on the part of the oppressed classes. Below is a list of some historical performances of the hidden transcript and everyday resistance: "In the case of slaves, for example, these stratagems have typically included theft, pilfering, feigned ignorance, shirking or careless labor, footdragging, secret trade and production for sale, sabotage of crops, livestock, and machinery, arson, flight, and so on. In the case of peasants, poaching, squatting, illegal gleaning, delivery of inferior rents in kind, clearing clandestine fields, and defaults on feudal dues have been common stratagems. " (Scott 188) While he gives examples of slaves and peasants -- which constitute the bulk on the book's examples due to the significantly more personal quality to their systems of domination -- the proletariat, or the working classes, under capitalism are also an oppressed class that performs public and hidden transcripts. The oppression of the working classes is less personal because instead of working under one master or lord, they work for various employers whom they are free to leave -- if they have another job, money, or are willing to live in poverty and possibly starve. However, Scott writes that "virtually every instance of personal domination is intimately connected with a process of appropriation" (Scott 188). We can also assume that the inverse of this statement -- that virtually every instance of appropriation is intimately connected with a process of personal domination -- may also apply. Under capitalism, surplus labor is appropriated from some workers in the working class in the process of production. Other workers in the working class may maintain these workers so they can keep producing surplus labor through what is often called reproductive labor, which is all the work required to give keep us healthy and educated, etc. In other words, the capitalist class materially appropriates a portion of labor, of time and vitality, from the working class. Then, of course, there are also regressive tax systems and a myriad of other ways to appropriate resources and wealth from the working classes. They are also symbolically taxed -- especially by the hegemonic idea that we live in a meritocracy and therefore our worth is correlated with our wealth and socioeconomic status. According to this idea of meritocracy, the fact that someone is poor or struggling is a mark of their inferiority. The working class is defined by material appropriation beyond the extraction of surplus labor. The working class is the class that doesn't own the means of production; it has long ago been appropriated from them by the privatization of lands and resources. They have nothing to sell but their labor, making them dependent upon the capitalist class as a whole (and it should be noted that the capitalist class is dependent on the worker to produce surplus labor that they can turn into capital). From here, it is not hard to imagine the ways in which the working class may then be personally dominated. Bosses, as capitalists or acting on behalf of capitalists, can and have exploited this dependency to abuse employees with impunity. A boss may ask for sexual favors, for extra work, demand specific acts of deference, etc. So it is not a question of whether the working class would constitute a dominated class in Scott's system, but there is the problem of finding as many performances of an hidden transcript, particularly among the more privileged sections of the working class (e.g. full-time workers with good wages and benefits). Scott argues that the dominated class is more likely to resist and perform a hidden transcript when domination is more personal -- when it attacks their very dignity. And, more importantly, the performance of a hidden transcript through acts of everyday resistance is more likely to be performed by oppressed groups who have very little power in the public sphere -- or by individuals in a situation in which they have little to no power. We, fortunately, still live in a liberal democracy -- albeit one that is under threat -- which means that public campaigns will constitute the bulk of the working classes' political life. Protected political liberties, such as the freedom of speech and association, means that resistance may take an open form in many cases. Clandestine resistance, which Scott calls the "infrapolitics" of the hidden transcript, is the strategy of dominated classes "under the conditions of tyranny and persecution" (Scott 201). In other words, the infrapolitics which are part of the hidden transcript are the clandestine, everyday resistance to various forms of oppression that would otherwise be too risky to the oppressed group to resist publicly. And, rather than acting as a safety valve that releases tension without challenging power, the hidden transcript and everyday forms of resistance often are the foundation and fuel to more open confrontation. Collecting workers stories have illustrated powerful instances of open resistance through campaigns and unions, but, even still, hidden transcripts emerged. It came as no surprise to me, given that only 6.7% of private-sector workers and 34.4% of public-sector workers are unionized in the United States. The percentage of workers in unions, private and public sectors combined, is 10.7% for 2017, meaning that 89.3% of the workforce in the United States is not unionized and, therefore, has little power and voice in the workplace. This very un-democractic situation that exists in the workplaces for the majority of workers means that, in most states, workers can be fired for any reason, that is, without just cause in union parlance. I did an interview with a worker employed by a local restaurant as a server who was laid off because her boss just decided one day that too many of their family members were working there. No family conflict or anything of the sort gave rise to the boss's sudden inclination, he just decided it was a good idea one day. Apparently, after telling them they were laid off, he expected them to continue working for two more weeks or so until they could find a replacement for them. Well, this worker decided that they had enough and left the job right there and then; they weren't going to give the restaurant extra time to find their replacement. And, like most cases of infrapolitics, this bit of resistance wasn't just a cathartic moment for them: this worker now wants justice. They want to see the complete end to all "at-will" employment. Everyday resistance is the fuel for organized and open confrontation, just as Scott argued. While researching oral histories of the working class, I came across an interview from a kind of worker that has some of the least amount of power on the job: the temp worker. Working for an employer on a short-term basis, often without any opportunities for advancement or benefits, there is little incentive for a worker to follow the various autocratic mandates of the workplace. The worker -- whose interview I found in Gig: Americans Talk About Their Jobs edited by John Bowe, Marisa Bowe, and Sabin Streeter -- shows a cynical awareness of his precarity. Rather than obediently accepting it or outright rebelling against it, he uses it to his advantage. He walks off the job the second someone aggressively bosses him around or treats him unfairly: no two weeks notice, no one week notice, no notice at all. Just walks off. Or, he leaves a job when he feels like it: takes a vacation on a whim. Or, he surfs the web while answering calls. Without the framework of domination and hidden transcripts, this behavior could just be written off as someone who is being an annoyingly bad employee. And that is true. But, it must be imagined that feudal lords must've found it obnoxious when their peasants returned to them inferior goods as rent, for example. We can applaud the peasant's clever act of minor rebellion -- that is their performance of the hidden transcript in the form of what Scott calls infrapolitics -- because we understand now, for the most part, that the relationship between the lord and peasant was one of hierarchy and domination: there is an imbalance of power. However, in our capitalist society, the guise of the labor market as something both employer and employee enter into as equals keeps us from recognizing that this too is a relationship of hierarchy and domination. We forget that if the worker does not sell their ability to work to an employer, they may not survive. The amount of the worker's time purchased by the employer belongs entirely to the employer, during which the worker has little has little say in what they do or the conditions under which they do them, save for some government regulations and any union presence to amplify workers' voices. In a temping situation, the work given is usually the most distasteful, the most tedious, monotonous, and least valued despite how much an organization may depend on it, and the temp worker is likewise devalued -- not even considered a real employee of the organization. Sometimes, the work is outright dangerous, as explored by a new documentary film on the temp industry, called A Day's Work. It is only after analyzing power and domination in this situation that we can see this worker's behavior as a form of silent, everyday resistance, a hidden transcript. This resistance can protect the worker's emotional and physical energy -- energy that they may then instead direct towards fighting for better working conditions, a union. To find everyday resistance among the working class, we need to throw middle class morals aside and recognize that an imbalance of power and exploitation are inherent features of the capitalist workplace. It should then be of no surprise that workers who have little to no voice at their workplace may quietly rebel. As a researcher of oral histories, one needs to analyze power -- of which, class is a strong indicator -- to find it. As an oral historian, one needs to suspend all judgement and establish trust with their interviewee: by revealing their everyday acts of resistance to you, they are trusting you to be sensitive with that information so they aren't fired or their reputation isn't ruined. Locating everyday resistance among the working class acknowledges their agency even when they have lost much of their power in the public sphere over the years: even though the percentage of unionized workers has been decimated over the last 50 years, that does not mean that the working class has come to fully consent to the whims of capital. The working class is still oppressed, and they still don't like it. With Scott's framework of everyday resistance, perhaps we can start believing in them again, and, if we are among them, believe in ourselves and use this fuel of resistance to organize and build power.

0 Comments

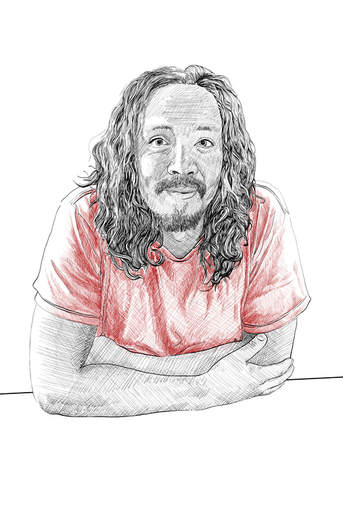

Bridging one's political work with one's artistic practice in a meaningful way is not easy. There are three general ways artists have built this bridge:

As my own practice has progressed, I have been trying to move from using just method #1, that is, making art with some political or social justice content, to using methods #1 and #2. And this past Sunday, Jan 28, I had the chance to finally bring an oral history project I conducted in Barre, VT as part of my book/zine project, Metamorphic: The Transformation of Work in Granite Town, to some amazing working-class activists and organizers in Barre, VT at the VT AFL-CIO COPE Conference. The conference was held in the Old Socialist Labor Party Hall in Barre, a perfect space for both the conference and my project. I called my presentation "Voices and Contours of Labor: Notes and Drawings from My Oral History Project in Barre, VT". "COPE" stands for the "Committee on Political Education". At the VT AFL-CIO COPE Conference, that usually translates to talking about issues that concern labor that are currently moving through the legislature. So, bringing interdisciplinary art into such a space can seem like a tangential diversion that may be unwelcome -- but, fortunately, that was not at all the case. After all, political education can encompass so much more than electoral politics. While I completely understand the importance of educating ourselves on what is going on in our state's legislature and putting pressure on our representatives to get labor-friendly results, I was also taught a broader and deeper understanding of political education through my work with the Vermont Workers' Center, The Poor People's Campaign, and the Popular Education Project (PEP). In doing political education work with these organizations, I learned about the fundamental social forces of capital and labor under capitalism and how they move and interact. Understanding this allows us to see not only the possibilities right before us but also those of the future. So, despite how out of the box my art and research is in such a context, I went and ahead and did my presentation. I explained how I became interested in Barre because of its radical labor history and because it is a case study in deindustrialization -- before the term even came into popular parlance. Barre, like all cities that are commonly associated with the term deindustrialization, was once known as a center of industry but is now more known for its stagnant economy and poverty. It is a case study in the tendency of capital to reduce labor costs. There are many ways capital has achieved this, but the most powerful way by far has always been through technological development. Globalization, which is also often cited as a means of reducing labor costs, is dependent on developments in information and transportation technology, without which it would be impossible to coordinate free trade across the globe. At the same time, in the midst of deindustrialization and rapid technological development, is the possibility for freeing up more of our day from waged work. I continued to explain that I wanted to go beyond what other oral historians had done when interviewing people about work: I wanted to not only ask them how they felt about the work they did, but how they would feel about not working -- or, at least, not working as much. Automation will continue disrupt the economy; and, with technology becoming increasingly capable of replacing everything from unskilled to highly skilled labor (as adeptly pointed out by Martin Ford in his book The Robots Are Coming), work as we know it in the form of the the full-time job and the 40 hour work week may become more of a rarity in the job market. That means we may have to rethink our relationship to waged work if we don't want masses of people to be left out in the cold void of long-term to permanent unemployment. Then, after having talked to everyone about automation, the future, and robots, I brought it back to Barre with the oral histories I conducted there. Given my time limitations, I shared brief quotes from three different people working in Barre, VT, extracted from hours of recorded material. Overall, some people readily welcomed the prospect of a "postwork" society with more free time for workers. Some less so. Regardless, most expressed a desire to work less. Here is what I shared: Ellen, Early Childhood Educator “I need to be working and making a difference. And frankly, if I didn't have to work and I could spend as much time doing whatever I potentially was qualified to do, I would totally do something that I feel passionate about.” “I think automating all jobs is a terrible idea. I think that's not allowing us to be human anymore. I do feel like a lot of the work that I've done has been very purposeful. It's not just about going to work to make the paycheck. You're doing what was meant for you to do, the reason why you were put here, essentially.” “Even if I won the lottery, maybe at first I would take a break for a period of time from work, but I would not want to just retire for the rest of my life.” Gampo, Granite Carver/Finisher “If my needs were sort of more balanced, maybe I'd be more generous with the commission work. And that would be kind of cool actually. Because right now in capitalist society, you kind of go after lots of money, like is it big enough? You have a very targeted capitalistic mindset.” “I think when people's needs are met, it would be more sort of communal. I don't know if communal is the right word. It would be where people would just have a little more care for each other instead of competition.” Sarah Miller, Diversion Case Manager  “My parents have been retired now for, I guess, my mom's been retired for 18 years and my dad was retired for 18 years before he passed. They have really rich lives. My dad volunteered, my mom volunteers. She's a fiber artist. She crochets, she knits, she does embroidery and wins awards for it. She quilts and she goes to church and she has really deep relationships. I feel like more of her life is meaningful. She has more meaningful moments in that regard.” “It would be awesome if we had four day weeks. Every time I feel like three days is so much better to reset yourself. I just wish we didn't have to do it so much, that there weren't so many trappings, because I don't think the purpose of us being on this Earth is to work. I think we're just supposed to be here.” As you may have noticed, I haven't finished the digital drawings of all the interviewees yet: Sarah's is still in-progress. So what kind of response did I get for taking everyone on a sort of wild ride into possible futures merged with good old fashioned oral histories? How well was I able to bridge my political work with my artistic practice? Well, I can't say for sure what everyone was really thinking. But, people seemed pretty interested, and my presentation stimulated some good conversations over lunch. The conversations confirmed my belief that people are hungry for political education that is artistic, interdisciplinary, and experimental -- even when it comes to liminal subjects such as automation and robots that seem to sit somewhere between reality and science fiction. I grant that my artwork may not be categorized as material for political education in the strict sense of being designed explicitly to explain certain campaigns or concepts. However, I think political art that is brought into political spaces (that is, art that at least combines methods #1 and #2 for bridging political work and art), can be a powerful form of political education. It can encompass more than a single campaign or issue and get us all to think about that which we take for granted -- such as the fact that we must sell our labor power in order to survive. "The mental battlefield is littered with old and entrenched values and ideas", writes Willie Baptist in Pedagogy of the Poor, a brilliant political educator and poverty scholar whom I've had the pleasure of meeting (Baptist 163). In the context of my project, I am dealing with old values and ideas around work, in which waged work is the only kind of recognized work and reigns supreme over all the other labor we do for each other and ourselves; over taking care of our children, family, and friends; over volunteer work in our community; over the work we do to educate and cultivate ourselves. "'Plowing the field' of old ideas is indispensable to "planting seeds" of new ideas" (Baptist, 163). Waged work doesn't have to monopolize so much of our time. The question is what would we do and what would become if we had more free time? Major structural changes in our economy are on the horizon. Radical labor leaders in Barre, VT fought for the 8 hour work day, and, almost a hundred years later, we are long due for another reduction in the workday while still retaining our standard of living. That's why for me, as a working class artist, bridging politics and art is not only possible but necessary for a progressive and just future.

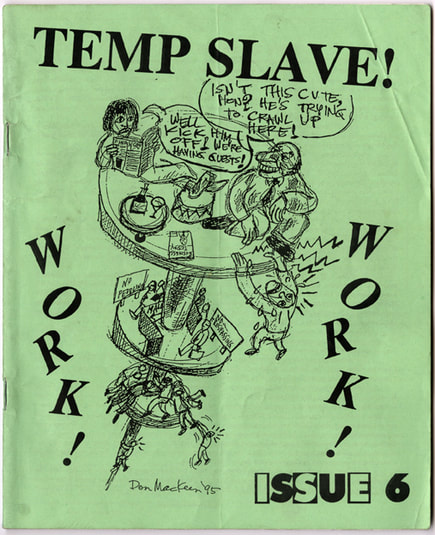

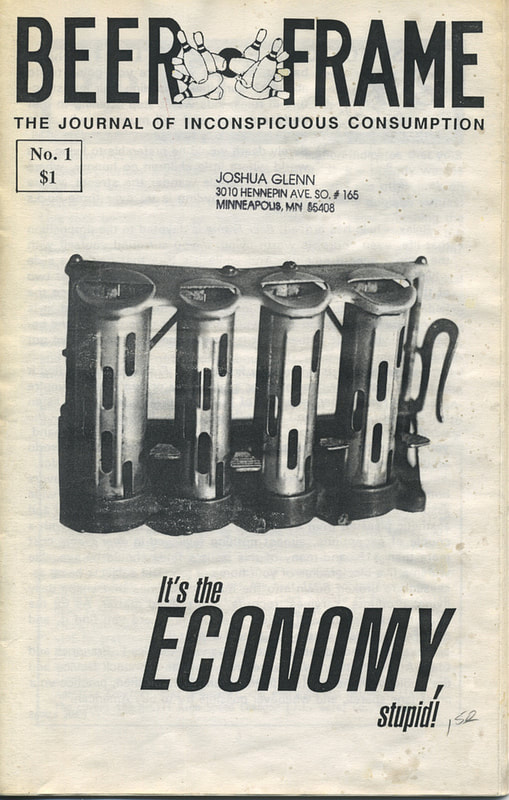

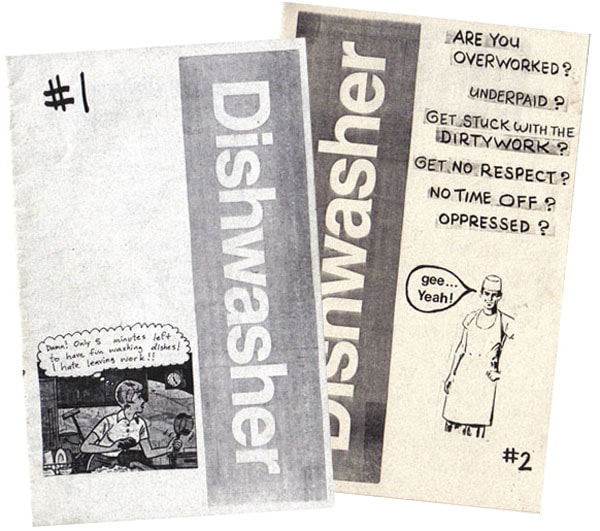

Coming from a background in the visual arts, I’ve always liked the idea of working with text and image, but it has taken me some time for me to think about what relationship between these two forms of communication would most powerfully give voice to what I care about. To better ground myself in the world, including the world of prose and ideas, I took a break from my visual art practice altogether. Some years later, I found myself working at an institution, Goddard College, that fully embraced an interdisciplinary approach to artistic inquiry. After a year of experimenting and searching at Goddard, I realized the way into developing a practice based on text and image has been around a long time: the way was through zine-making. First, putting text in relation with images is something that inevitably happens, even within a strict visual arts practice. Inevitably, the artist has to contextualize it with words in order to be taken seriously, and, if it is being shown, someone is going to talk or write about it eventually. Some artists may shun text for the way it delimits an image, but it is inescapable. My reason for moving towards a practice that integrates text and image, with an increasing emphasis on the former, is precisely because I want it to be somewhat delimited. Of course, I don’t want to be didactic, but instead of offering a wide channel for interpretation, I want to offer a deep channel -- breadth and depth, ideally, but if I have to choose, I choose depth. I want to make work that is moving, critical, and thought-provoking. But I want to make work that is clear and sure of itself such that it cannot be appropriated by those who would wish to reduce it to milquetoast. Even more, I want to create art that gives history and agency to those who are the makers of history: the working classes. Those are the abstract formal reasons for my turn to text, but the political nature of my subject matter naturally inserted itself into the history of zine-making, or, more broadly, the making of pamphlets and leaflets. Zines, while mostly known today for their association with the riot grrrl subculture, are part of a wider history of self-publication, harking back to political pamphlets and leaflets. Within the United States, one of the most well-known political pamphlets is Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, which made a popular and forceful argument for the independence of the United States from Great Britain. Common Sense was read and distributed widely; it found audiences everywhere from drawing rooms to taverns, its words heightening the zeal for self-determination and freedom. Surpassing the influence and fame of Paine’s Common Sense is arguably The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx. In February 1848, The Communist Manifesto began as a 23-page pamphlet published by the Workers' Educational Association: this manifesto became the seed of not only one revolution but many and continues to be read in revolutionary movements to this day. Fast forward, Zines and zine culture, like the political pamphlets and leaflets that came before them, continued the tradition of printing dissident ideas and voices. However, unlike the two aforementioned political texts, the zine cultures that arose in the 70s, 80s, and 90s that are most familiar to us today were less interested in mass distribution and appeal than they were in cultivating subcultures in which individuals with identities and politics repressed by or adversarial to those of the mainstream could find reprieve through self-expression. The zines coming out of what was labeled the riot grrrl subculture, for instance, appealed largely to third wave feminist sensibilities by emphasizing the diverse, individual experiences of sexism. As Stephen Duncombe, Professor of Media, Culture and Communications at NYU and author of Notes from the Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture, writes “Zines put a slight twist on the idea that the personal is political. They approach political issues from the state to the bedroom, but they refract all these issues through the eyes and experiences of the individual creating the zine.” Rather than political manifestos aimed at fomenting a societal revolution, zines coming out of the subcultures such as riot grrrl often used their medium to instead create intimate communities of support and resistance. One of the first zines I picked up as a teen hanging around at punk shows was Support by Cindy Crabb and Doris Zine. The zine is composed of a collection of written and collected pieces of advice on supporting survivors of sexual abuse and preventing sexual violence. It has helped me understand both myself and others. It has also taught me how to become a better listener and friend -- again, to both myself and others. It was written to be an invaluable healing tool. It was not written to analyze the long history and structure of patriarchy in an attempt to outline how it may be overthrown. A simple wikipedia search on zines will highlight their connection to riot grrrl and a few other subcultures, but less known is the frequency with which zines were used to protest the conditions of work under capitalism, made worse by the shrinking of the welfare state and the rise of neoliberal, pro-market politics beginning in the 70s. As a wage slave educated in Marx’s political economy who entered the labor market in the midst of the 2008 financial crisis, I knew that the increasing sense of impoverishment and alienation I experienced was shared by many and part of paradigmatic shift in capitalist development that was leading us all towards a more precarious future for ourselves and our planet. I also knew this had to inform the content and form of my renewed artistic practice. I had already started my serial book project, Metamorphic: The Transformation of Work in Granite Town, to be released chapter by chapter as zines, before I knew about such gems as Dishwasher Pete, Welcome to the World of Insurance, Temp Slave, and ExtraTuf, all of which offered varying acrimonious and cathartic critiques of work and the work ethic. It was the Stephen Dumcombe’s Notes from the Underground that introduced me to the world of zines about work. According to Duncombe, the zine was really the perfect medium to channel the frustrated creative and intellectual energies of workers disillusioned with their job and the American Dream of upward social mobility. “In zines, writers present the real story of the work they do,” writes Duncombe, “...cutting through the crap...about the bright future in the high-tech age.” Zines, being self-published and easy to produce, offer space to dissenting voices who may otherwise find themselves censored or dismissed by mainstream media outlets charged with upholding the ideology of the work ethic. With wages stagnating, worker power in the form of unions diminishing, and the constant deskilling of labor through technical and organizational innovations, zine writers feel there is no “dignity of work” to preserve. But instead of grieving their low-pay and lack of power at work, many zine writers mock the hypocrisy of the social and economic relations at work. In a labor market where the company and the boss expect their workers to give their all but offer little in return by means of security, benefits, and wages, a mocking, apathetic, or hostile reaction is not surprising. A brilliant example of cynical humor illustrating this attitude shows up in a column titled “Problems and Solutions” in Dishwasher Pete: “PROBLEM: You’ve been breaking a lot of dishes at work” “SOLUTION: What’s the problem?” That said, zine writers are not against work in the abstract; contra to the DIY aesthetic present in many zines which can sometimes give them an “unpolished” look, creating zines requires a lot of intense focus and work. Unlike the day jobs that become the subject of many zine writers derision, zine creation is an act of unalienated labor that is enriches the heart and mind and is therefore relished. However, compared to more traditional hobbies, zines self-consciously emerge from adversarial conditions. An interview with Pinto editors Sara Lorimer and Paul Schuster clearly makes this connection: “Sara: You know I’d never thought about doing a zine until I started working at that awful record store. There’s gotta be some sort of connection there -- between that being such a stifling place and needing an outlet for creativity. Paul: Yeah, maybe it’s a reaction to the shitty working environment we were all subjected to…” Zine writers, whether or not they were writing about work, are carving out their own “little world, in which [they] can experience the revolutionary pleasure of thinking for [one]self”, writes Mickey Z, creator of Flaming Crescent zine. When I started my book project and decided to release each chapter as a zine, I also wanted to make space for the complicated -- and sometimes angry -- thoughts and feelings we all have about our jobs but must bury in order to appear as functional workers and citizens in a capitalist society. But I also wanted to connect these feelings to the why: Why are so many workers feeling angry and alienated at work? Why is social mobility decreasing and inequality increasing? I’ve read plenty of explanations from mainstream economists, from Thomas Friedman to Robert Reich, and while they may at times make valid points, their structural analysis falls short -- mainly due to their incomplete understanding of how value is created -- when compared to the master of political economy, Karl Marx. More importantly, Marx developed his theory on the basis of those very questions, as Terry Eagleton writing for the Chronicle of Higher Education has pointed out: “There is a sense in which the whole of Marx's writing boils down to several embarrassing questions: Why is it that the capitalist West has accumulated more resources than human history has ever witnessed, yet appears powerless to overcome poverty, starvation, exploitation, and inequality? What are the mechanisms by which affluence for a minority seems to breed hardship and indignity for the many? Why does private wealth seem to go hand in hand with public squalor?...” I’ve read through Capital and other works by Marx by myself and with others. And, as much as I personally loved reading almost a thousand pages critiquing capitalism, I know that we first experience capitalism in a very personal way. We need to awaken both the heart and the mind. But while we may first enter the realm of the political through our own experiences, through our heart, we will never move beyond individual transformation if we don’t connect it to a larger analysis. It is with a unifying theory that the personal becomes political. So here I am, releasing my first series of zines. Of course, I could just as easily write a series of blog posts, like this, which shares the spirit of the DIY confessional with zines. In fact, many have said that with blogging, the zine is irrelevant in this day and age. And yet, I couldn’t disagree more. Aside from the rich history of zine making, printed books and zines are more intimate; they can be touched; they take up space. A blog is at once everywhere and nowhere. It is easier to curl up with a zine and let oneself open up to it like an old friend. On paper, there aren’t the distractions of dozens of open tabs and apps. Not to mention, my inner teenage punk is totally excited about this -- and I hope you are all too. For all that, while this project is will situated in the history of zines, I also hope to go beyond my own “little world” of autonomous thought and, instead, create many, connected worlds for free thought through the collection of oral histories from workers located in Barre, VT, which will constitute one of the chapters of my book and a zine issue. I’ve chosen Barre not only because it has shaped the place where I currently live but because it has a unique, radical history of class consciousness and organization with the aim of creating a freer world. They have questioned the very notion of a world where the many had to work so hard to live no matter how much wealth they produced for others. They knew that justice did not equal just having a job but having control over that job; and, more importantly, having free time to do all the unwaged caring, learning, and loving that are necessary for living as a human being. Through original illustrations, collected interviews, and personal meditations at the intersection of geology, political economy, and psychology, Metamorphic will make the personal political.

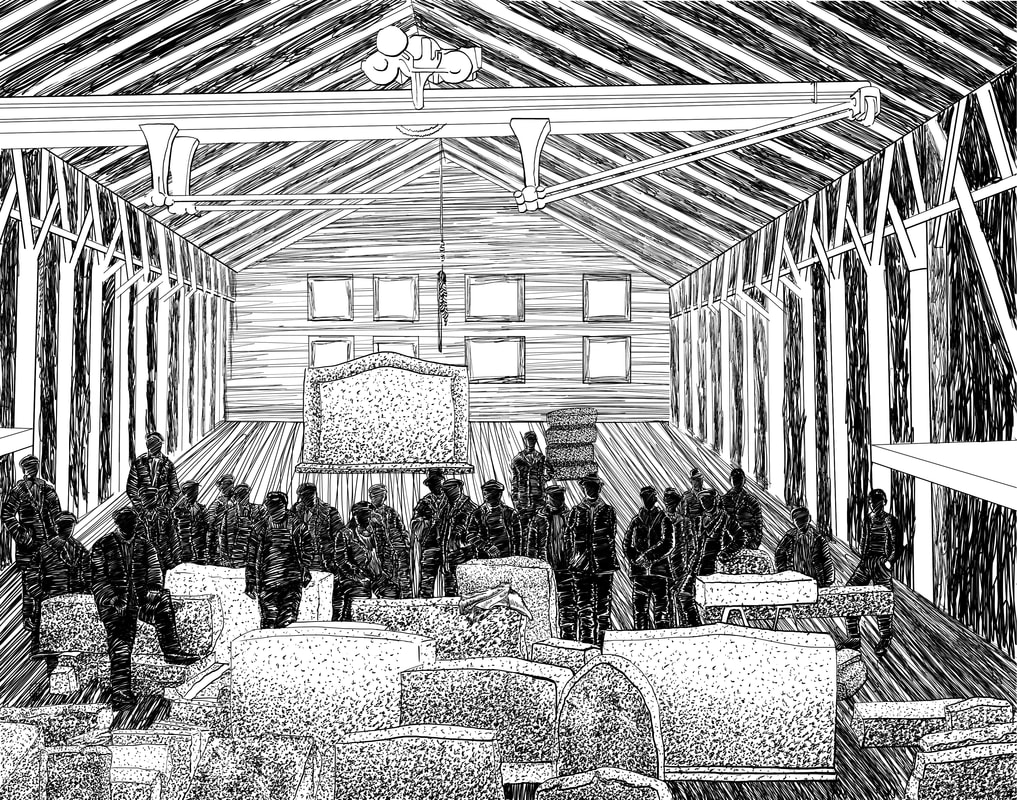

The following is a selection from Metamorphic: The Transformation of Work in Granite Town, Chapter 1 "Everywhere and Anywhere". The entire chapter has been released as a zine issue, which you can order from me by contacting me. The zine is a suggested $1-2 donation plus shipping.Metamorphic rocks have resided in different geological settings in their journey of becoming what they are. They become their own unique hybrids of the places they’ve lived. They record more than a journey; they record change. Not all rocks are metamorphic -- granite is not a metamorphic rock -- but all kinds of rocks can become one. “All science would be superfluous if the outward appearance and the essence of things directly coincided.” - Karl Marx The empty shops, boarded up houses, and smokestacks of Binghamton and Baldwinsville, New York -- most of them silent and statuesque in their new function as memorials of another time -- impressed my childhood mind as enigmas. At one time, they contained and supported lives. Why didn’t they anymore? I’d take long, clandestine bike rides out to them, get close to their facades, daring them with my gaze to reveal the calamities they contained; I intuited the present dangers of drugs and violence that grew in their darkness to be natural extensions of the troubles that led to their current state of dereliction. But I never went in. I never uncovered their particular histories. My grandparents used to work behind some of those factory walls. Through their toil, they fed and housed a family, but the work also gave them much pain, which was made known through frequent complaints of achy hands, backs, and feet from standing on concrete floors all day, making the same motions over and over in sync with the machines. But much of their interior lives and feelings were hidden behind a wall of stoicism. In school, I was taught that we are on a one-way journey called progress. The strained optimism of my parents tried to validate this claim. When I found my mom crying late one night after she finished her shift at Burger King, the only job she could find at the time when our family desperately needed the extra money, the idea of progress became a prevarication that sank into the pit of my stomach. I knew a little about how it must have hurt because of the cruel assumptions my peers made about her and, by extension, me -- namely, that we were struggling because we deserved to be. My mother is bright. She won awards for her mathematical abilities in school, but she did not have the privilege of a college education. From then on, I learned to see the contradictions in everything. When I ended up in Central Vermont eighteen years later, the neat towns nestled in between the mountains appeared as if they magically arose sui generis without the powerful force of industry. After almost six months of unemployment I found myself working as a VISTA - a Volunteer In Service To America. Vermont’s Twin Cities, Montpelier and Barre, became my home. I lived most of my life in cities where people always outnumber animals, and perhaps that was true of these small towns as well, but it certainly didn’t look like it. Montpelier was the state’s capital, at least, giving it importance by default. Barre was much more mysterious and obscure. Up and down main street, you find the standard small town America offerings alongside a smattering of creative outlets and stores that have somehow withstood the test of time: a gas station every several blocks, a dollar general, a couple convenience stores, a mechanic’s shop, car parts stores, hardware stores, a diner, and a couple of nicer restaurants and shops that probably mainly serve folks from out of town, cooperative artist’s studios and a gallery, a shop for shoe repairs, and a shop for sewing services. Just driving through Barre, you wouldn’t think there is this big hole in the ground nearby that birthed some of the most revered buildings and monuments in history, some of them sitting in Washington, DC: the Smithsonian Institution, Union Station, and the General William Tecumseh Sherman Memorial which is right next to the White House. Or that its granite can be found on almost every battlefield and national cemetery in the nation. Or that it once churned out an enormous amount of money and profits -- enough to make this town into a capital of industry, the Granite Capital of the World. Such auspiciousness drew people from the other side of the ocean, predominantly Italy, Scotland, and Spain. The cost of this outward progress was paid in flesh: the quarry owners swallowed young men whole in their pits and sheds. Widowed wives had to hustle to keep their families alive, running shops and restaurants (sometimes out of their own homes), taking in boarders, furtively making grappa and spirits for the wealthier clientele coming in from neighboring Montpelier, bearing the death of their husbands in the constrained silence of hard labor. There are hints of this history, even on Main Street: a restaurant named “The Quarry” and a statue of an Italian stone carver dedicated to all the workers in the industry. The statute reads as a memorial, but the granite industry is not wholly dead in this town. The traffic whirs by with threatening speed -- commuters travelling between the twin cities, not heading to the quarry or manufacturing plant. I go against traffic towards Graniteville, where Rock of Ages -- now owned by the Canadian company Polycor, Inc, which owns 32 quarries across the North America -- still operates a memorial manufacturing plant and a quarry. Idling at a traffic light, a man holds a cardboard sign that reads “Homeless, need help until SSDI comes in. Every bit helps.” A large, black crow gallantly flies ten feet above me, carrying a large stick in its beak. She or he -- in the society of crows, there aren’t rigidly defined gender roles when it comes to homemaking -- is trying to build a home in which to raise the next generation. Half a mile further down the road, a couple of construction cranes are at work fixing power lines near a subdivision of homes. For us, nesting season never ends. I continue driving. The sky has been relentlessly gray today. Gray skies have a way of quieting everything around you. Nature pulls a blanket of clouds over us and asks us to rest. But, of course, we cannot. We need to make things, make money, make nests. The crow must do this, must live day by day, but even with all of the extra stuff we make, all this surplus, most of us also live this way. There are only a few branches on the road around us, but, sequestered away in the woods there are a countless number of them. Away from the town, ensconced in a congregation of trees stands a large generic-looking modular building, the Rock of Ages manufacturing plant. The Visiting Center, with its stylish modern-looking architecture of sweeping geometric shapes that are slightly distorted for a postmodern yet conservative effect, contrasts with the factory, which is like any other in its extreme efficiency of form. Tourism and work. Luxury and functionalism. Consumption and production. Today, I am the tourist, the consumer. Tomorrow, I will work and produce -- not here, but as a secretary of sorts at a small college. I walk up to the Visiting Center first and see through the windows that it’s very dark inside. I give the doors a try. They are locked. No signage, hours, or writing is present on the door. Perhaps I have the wrong entrance? Walking around its circular structure, I step off of the portico made, of course, of granite and onto the green-brown earth that sucks me into its wet body. Another door and a little sidewalk tell me this is the main entrance. It is also locked, but there is a sign this time reading “The Visiting Center will be open starting May 15. All other visitors are welcome to go to the self-guided factory tour next door.” So that is where I go. An effective sign. The self-guided tour entrance opens into a small lobby with a video on a loop displayed on a mounted flatscreen TV. Old and new advertisements for Rock of Ages graves, or “memorials”, flank the TV on both sides. In the video, a couple talks to me in terms of “we”. The man and the woman are white, in their 60s, wealthy as indicated by their dress and the fact that they are shopping for grand, ostentatious mausoleums. The mausoleums reach for the grandiosity of the Parthenon, for the height of Greek architecture. They are proud, exuberant -- but lest one think their sumptuous taste be an unflattering sign of egotism, the couple looks at me from the screen and says, “We want a beautiful place for our children to remember us in.” The couple gets a form of immortality -- guaranteed by the Rock of Ages Certificate of Craftsmanship -- and the next generation gets a memory, a heritage, a sense of pride. Leaving the lobby, I walk up a flight of stairs to the observation deck where I will be able to see the entire factory floor from above. Here I was met again with the monotonous buzzing which I noticed when I was outside but almost forgot in the quiet lobby with the nice couple endlessly shopping for their memorial. In the video, the couple went to the factory floor, too, showing a subdued admiration for the quality and skillfulness of the machines and workers. I carried that feeling in with me when I walked up to the observation deck. But for the first several minutes, all I could do was stand stunned. It was the grinding and droning, the tickling of dust in my nostrils, the smells of wood and oil -- of industry acting on the senses. A wall of pictures, text, and a diagram told me what was going on before me through faded paper and frames than hung crooked and tired on the wall. Over 200,000 square feet spread out below me, crowded with stones, mammoth ventilation systems, little metal sheds with computer terminals, columns laid on the floor for mausoleums, modest headstones ready for shipment with paperwork strewn across them. In the right-hand corner closest to the observation deck is an area that resembles an artist’s studio and, indeed, this is where the few remaining carvers work. Naturally, Rock of Ages wants its visitors to see this area the most clearly. Tucked away far from the purview of the tourist, the slow back a forth motion of a machine above a steel bed tells of an automatic polishing machine. Customers want to see that care -- that a human touch -- is involved in this most solemn of purchases. We want some distance between ourselves and the machines, because it is becoming clearer and clearer with every innovation that they, and not our children, are the future.

|

AuthorI am an interdisciplinary artist who brings together images, narratives, and social theory to reveal the lived and imagined systems that construct our lives. Archives

September 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed